Photo Provided by Blue Engine

For foundational context, please be sure to review our Landing Page.

Blue Engine has centered equity as critical to their mission since the founding. Throughout the organization’s growth, however, Blue Engine has experienced an evolution of their values around equity, and expanded to thinking critically about diversity and inclusion as well. We follow this organization’s powerful journey in navigating these challenging questions, and their direct and significant impact on Blue Engine’s identity and work.

Curious about what’s happened since the moment in time of this case study? Watch our webinar with leaders from Blue Engine and the co-authors of the cases here!

Blue Engine partners with schools to unlock human potential.

“We support teams of teachers working in historically oppressed communities to reimagine the classroom experience for all students.”

Their model is based on a core belief that teams can enable outcomes that individuals alone can’t achieve. Blue Engine believes that when teachers work together on a team, they have more capacity and ability to connect with all students and provide instruction based on students’ needs. Classrooms become places where students thrive academically and are seen and heard.

Blue Engine’s vision is that by 2040, the public education system has “integrated mindsets, practices, and structures such that multiple adult classrooms are serving the needs of all students, creating a more just and inclusive education system.”

Blue Ridge Foundation in Brooklyn issues grant to launch Blue Engine

First employee hired

First team teaching pilot launched in one school in Washington Heights with 200 students and 12 Blue Engine Teaching Apprentices (BETAs).

15-20 core staff and ~80 BETAs

BE worked with ~1,900 students in 24 classrooms across nine school partners.

20 Core staff.

Over the past nine years, Blue Engine has developed a research-based team teaching model. Working in partnership with teachers, coaches, and school administrators, Blue Engine “builds the capacity of teachers and schools to create structures and implement research-based practices that leverage multiple adults. In turn, students have access to supportive and challenging classroom experiences that affirm who they are and meet their unique learning needs.” Blue Engine’s goal is to “create conditions where true differentiation exists for ALL learners in a classroom by leveraging the power of multiple adults in each classroom.”

Blue Engine’s AmeriCorps model places AmeriCorps service members — Blue Engine Teaching Apprentices (BETAs) — alongside lead teachers on classroom-based teaching teams.

Blue Engine’s co-teaching model supports existing teams of co-teachers in schools.

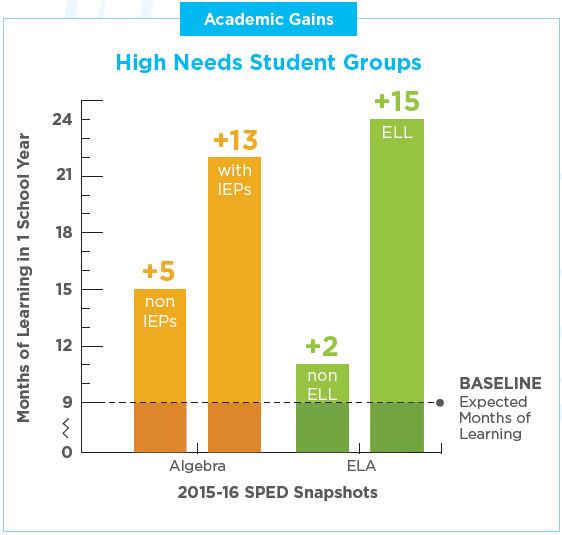

Students in Blue Engine classrooms are demonstrating significant academic gains in one year.

Graphics Provided by Blue Engine

90% of students in Blue Engine classrooms report a positive experience.

Graphic Provided by Blue Engine

70% of lead teachers believe working with Blue Engine improved their perspective about what is possible for student academic achievement.

Graphic Provided by Blue Engine

It was spring 2015, and Blue Engine was facing a moment of reckoning.

New Chief Operating Officer Anne Eidelman — now CEO — joined the 22-person team for an all-staff meeting. Erick Roa, then Site Director, spoke up. He named something he and others had mentioned before: The way Blue Engine measured outcomes for kids was warping incentives for their classroom teams.

“I was pushing back on some of the practices we had — we were specifically told to focus on students who were in the middle and high areas, on the cusp of passing exams or going to college, and the kids who didn’t have a chance, as perceived by the data, were not a priority.”

—Erick Roa

As a man of color who grew up in New York City public schools, Erick had lived experiences similar to those of the students Blue Engine served. He elevated two pushes: that Blue Engine’s approach wasn’t inclusive of all kids, and that they were perhaps systematically excluding the students who would most benefit from Blue Engine’s services. He then said something that stopped the team in their tracks:

“If I had been a student in a Blue Engine classroom, I would have been overlooked.”

—Erick Roa

The way Anne remembers it, they had a choice in that moment — to speed past the discomfort in the air and get back to the planned agenda, or to pause and dig in. The staff chose the latter, breaking into two groups to share, ask questions, and process what this critical observation meant for Blue Engine as an organization. “We had to look ourselves in the mirror and realize that despite our best intentions and articulated beliefs, we were perpetuating some of the oppressive systems that we were trying to break,” Anne describes. Grappling with this realization brought the group a mixture of frustration, anger, confusion, defensiveness, guilt, and shame. Blue Engine founder Nick Ehrmann was in the room, and he remembers the moment similarly.

“Maybe we never would have gotten to where we got [without his voice]. People — not me, frankly — who recognized and acted on their instincts were extremely instrumental. Do we serve some kids or all kids? Period. Depending on our answer to that, we need to tell the world, ‘Hold us accountable for this.’ It was this spectacular and really complex, open discussion...that spilled into an org-wide reconstitution.”

—Nick Ehrmann

Blue Engine chose to “pause and dig in” to that “complex, open discussion” not just for a moment in a meeting, but for the long term. As a five-year-old organization, Blue Engine entered a yearlong strategic re-visioning process, conducting internal research and holding conversations across stakeholder groups to bring greater clarity around their beliefs and what the organization was trying to achieve. It was that staff meeting moment that catalyzed newly elevated conversations about inclusion and equity — within both the organization and the classroom.

But this wasn’t the first time a person of color on staff had raised these concerns for the group. Why was it a moment of reckoning this time? We went back to the beginning to find out.

Blue Engine was founded by Nick Ehrmann, a former Washington, D.C. teacher who began his career with Teach For America. Nick’s doctoral program in sociology provided a researcher’s lens through which he viewed questions of diversity, inclusion, and equity, and he wrote a dissertation exploring “the negative effects of academic underperformance on the transition from high school to college.”

When he founded Blue Engine in 2010, Nick says he had an academic understanding of systemic racism and the issues his colleagues of color were raising:

“I think that there’s a certain level of safe distance that I was afforded by having what I thought to be a very good academic sense of what we were talking about...I’ve been exposed to a lot of conceptual underpinnings of institutional racism...I wrote my senior thesis in undergrad about white supremacy and had already been through a really long, very personal journey away from the sort of toxic ideas around a savior complex...One of the blindspots is that somehow that inoculates leadership from the lived experiences of people who work there.”

—Nick Ehrmann

The work for Nick and Blue Engine has been in part about going beyond an intellectual conception of power, privilege, and racial identity. This growth involves unpacking dimensions of cultural identity and listening to the lived experiences of people of color — in both the organization and the classroom — and codifying those lessons into bedrock guiding principles.

In Blue Engine’s nine years as an organization, they’ve experienced some profound moments of shifting culture, which only intensified in that 2015 all-staff moment of reckoning. What were some major themes and lessons up to that point and in the years since?

We’ll explore each of these themes in greater depth based on what we heard from Blue Engine.

In 2014, Aisha Chappell had some serious concerns about staff of color disproportionately experiencing disciplinary actions. She believed there was a disconnect between Blue Engine’s stated values and how those values were playing out: “[I felt like] this is a problem, that we’re not talking about race, and I think there are some unconscious biases that we’re projecting in the work that we do.”

She went directly to Nick Ehrmann, CEO at the time, to share her thinking. When she raised these concerns around inclusion and equity, she felt like they landed with Nick.

“[He] really heard it, and we came up with the fact that someone externally should support [us] to think more about diversity, equity, and inclusiveness work,”

—Aisha Chappell

Nick appreciated the push, saying, “Aisha was very vocal in a very productive and challenging way.” Her interruptions — both directly to Nick and publicly with the broader team — led Blue Engine to bring in an external facilitator to help them begin some of the individual and organizational work. As a result, the team developed a foundational value called their “multicultural worldview,” positioning Blue Engine as an actively anti-racist organization:

Graphic Provided by Blue Engine

Next, Blue Engine doubled down on expectations that all staff would demonstrate this competency in internal as well as field-facing work. This included engaging in all-staff discussions — both to create common language, and to support each other in building skills to live out their values. In addition, Blue Engine raised the bar for incoming staff by beginning to ask candidates more explicit questions about their willingness to engage in DEI work.

Meanwhile, the organization intensified their commitment to increasing the racial diversity of staff and BETAs. As part of this commitment, Blue Engine revamped their recruitment and selection processes, requiring that finalist pools for staff positions be at least 50% people of color before moving forward to a hire. The organization’s actual demographic diversity increased, and staff perceptions of recruitment and selection efforts reflect progress:

It was Aisha’s initial push in 2014, and leadership’s willingness to listen and respond over the next year, that created the space for more voices like Erick’s to be brought into the organization.

We heard many Blue Engine staff name the role that Nick and Anne’s leadership and commitment have played in pushing DEI work forward. Staff see them as leaders who are committed to Blue Engine’s explicit anti-racist values and who are willing to model by jumping in to do their own identity work. According to the Promise54 DEI Staff Experience Survey and follow-up interviews with staff, Nick and Anne have set a tone with the team:

“My perception is that [Nick] was super open to [change], wanted to poke holes in all the right ways, and he had blind spots...but certainly, he created the spaces for us to interrogate where we had been for the last five years and what the different sets of choices were that we wanted to make for the next phase.”

—Anne Eidelman

“Anne really sets such a great example of taking feedback — she welcomes...tough conversations, and knows that’s what we have to do to move forward. I have felt like I can go to the top person and have a challenging conversation with them and be received with open arms.”

—Lindsay Kent

Both leaders have shown a strong learning orientation. Nick recognized that he had a lot to learn and opened himself up to the process. Similarly, as Anne joined the organization in 2015, she reflects that she didn’t want to come in determined to advance a preconceived agenda — she wanted to listen and learn. Anne and Nick describe their own roles as white leaders who recognized they needed help to interrogate their own biases and privilege:

“I didn’t decide one day that we should initiate this — I wasn’t leading in that way. I was actually responding and trying to piece together what I’m hearing from the organization that was well overdue and needed to happen. I needed to make sure it was resourced, but then I had to get out of the way...learning how to stop talking, or learning to create space in all-staff retreats. I couldn’t show up as a type A leader or, even worse, an extremely defensive participant...Every time we were together, I tried to check myself and be open to the ways that ultimately I and other people have been bystanders in a process that wasn’t working well, or in an organization that wasn’t aligned with itself. It can be hard, but it’s not about my feelings or my failings. Ultimately, this organization has the resources and the brilliance and the capacity to confront and tackle these things.

—Nick Ehrmann

“I’m aware of my blind spots as a person who identifies as white, and feel very lucky and grateful to be working with a leadership team who is diverse by race (although not by gender). I see my role as constantly trying to keep this at the forefront of choices — so that we don’t miss blind spots. I surround myself with people who have different perspectives and experiences than me.”

—Anne Eidelman

Nick and Anne have also shown an openness to the inherent difficulty of culture shift, acknowledging their human imperfections as they roll up their sleeves to do personal work alongside staff.

“I remember when we were unpacking our own definitions around power and privilege, [Nick] was also unpacking alongside the staff. Having to sort of sit there and own and unpack his own identity in front of everyone for the first time, AND talk about the whole organization — that took a lot of vulnerability from our leadership team and I give them so much credit for that.”

—Jessi Brunken

Leadership and staff alike describe Blue Engine as a learning organization and a place where they want people to show up as humans capable of growth.

While white leadership has been very receptive to feedback, they’ve remained reliant on individual pushes from staff of color, creating an additional burden for those from already-marginalized backgrounds. It was Aisha Chappell (a Black woman) and Erick Roa (a Latino man) who spoke up and prompted Blue Engine’s initial efforts to diversify the team and to reexamine their relationship with inclusion and equity. Erick put this burden into words:

“It was mostly folks of color — I was the only person on the team that went to NYC public schools at that point, and was the only person who looked like me at the org at the time. We didn’t have a bunch of diversity on the team at the time. Very similar to what I’ve seen in many organizations, it takes the folks who identify a certain way to raise issues that they see...I feel like for a lot of people it’s just exhausting. You want to work for an organization that shares your values.”

—Erick Roa

Staff identify Blue Engine’s size and sense of personal connection as critical in creating high-enough psychological safety for these conversations to take place.

“It’s a very collaborative place...it’s in part possible because we are still a relatively small organization. There might be things that are not transferable to larger organizations. We’re still in a place where we can get in a room and hash a decision out collectively.”

—Seth Miran

“I haven’t seen many organizations where people feel comfortable being uncomfortable. For me as a person of color to feel really listened to was powerful. I didn’t feel tokenism either…. We naturally care about each other.”

—Sarah Fuentes

Staff recognized the importance of relationships — like those among Aisha, Erick, Nick, and Anne — in order to engage in the hard and messy conversations around DEI. In many ways, honest, collaborative relationships laid the foundation for this work — but it didn’t end there.

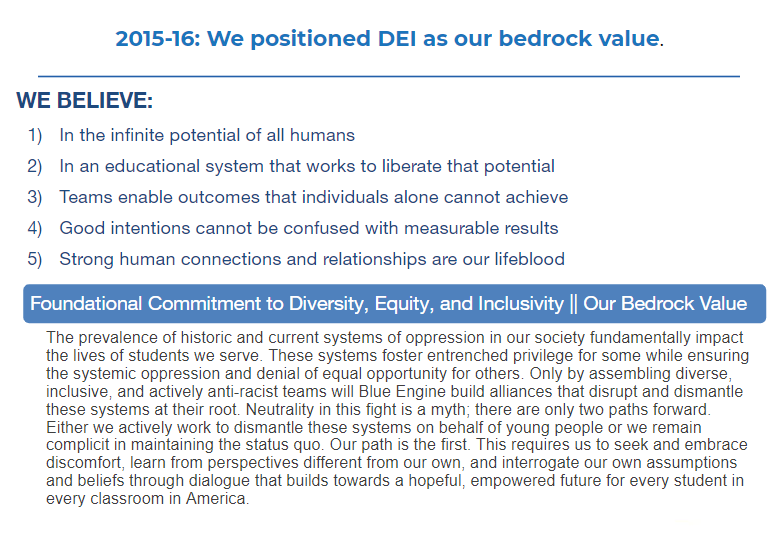

Self-reflective leadership, staff of color naming gaps, and relationships within the organization helped Blue Engine stop and take a hard look at their DEI values and practices — but the work had just begun. In the year following that staff meeting in 2015, the team revisited Blue Engine’s core values and strategic core, rearticulating their fundamental definitions of success and the values underlying those definitions - all with DEI as an anchor.

The first phase involved personal work and conversations on a variety of “DEI topics”. With the help of an outside partner, the team recognized the need for clarity of the organization’s beliefs about diversity, inclusion, and equity. Through a series of externally facilitated all-staff workshops and conversations, Blue Engine developed a powerful bedrock value statement around DEI in 2016:

Graphic Provided by Blue Engine

With this bedrock belief as a foundation, and with Erick’s prompting in mind, Blue Engine had to consider a new approach to serving students and measuring the success of the program. One staff member reflected:

“I think [Erick] sort of forced us to have difficult conversations, like talking about the way we used to measure impact for students and the way we served students — we focused a lot on students ‘on the bubble.’ We were super goal-oriented, and he really helped us identify the problem there and helped us think about the way we could measure impact more holistically...”

—Anonymous Staff Member

Previously, Blue Engine had measured success through college access for students, and stopped there. The organization had been counting “threshold” measures — how many students were college-ready vs. not — and that focus led to more attention for “bubble students.” Bubble students had previous scores that were close to passing, but not quite — hence the “on the bubble” terminology — so Blue Engine focused their resources and energy on supporting this subgroup. This unintentionally led the organization to de-prioritize students who were farther away from that “college-ready” threshold.

“We incorporated this lens of what it meant to have threshold [metrics] as our north star [in]to the strategic conversation that then took place over the next year...That set of strategic conversations had us overhauling our value statements, outcomes and intended impact, rearticulating our values.”

—Anne Eidelman

Ultimately, Blue Engine shifted their metrics and language from a threshold-based conversation to one focused on the growth of each individual student, regardless of their starting point. This represented a huge shift for Blue Engine, but one that allowed the team to feel more aligned with their inclusion and equity values.

“You don’t just decide on a whim to change your metrics. It’s an enormously painful and drawn out — and, in some ways, liberating — process for the people involved.”

—Nick Ehrmann

With leadership and staff commitment, as well as aligned values, strategies, and metrics in place, the question became how to translate all this to Blue Engine’s day-to-day work.

Anne first recognized how their core values could be open to interpretation without a clear direction: “We had this beautiful bedrock value of DEI, but if each staff person were to tell you what that actually meant for the organization, it would be totally different.” Recognizing shared values around DEI, while important for Blue Engine, didn’t guarantee that individual staff knew how to operationalize those values. Staff expressed that the application of “DEI work” felt scattered and spotty, left up to individual interpretation and locus of control, without the guidance of a clear overarching plan.

“There was a lot of energy [around DEI], but people didn’t know how to incorporate it into their work...it felt like DEI was all over the place and in everything and not...purposeful and strategic. People might have been overwhelmed with how much they were seeing it everywhere.”

—Stephanie Durden Barfield

Much of the unevenness may have stemmed from the challenge of people coming to DEI conversations at different points in their personal identity development. Anne described a range of experience that was difficult to accommodate — from those who were brand-new to the work of diversity, inclusion, and equity to those whose lived experiences led to a sense of exasperation.

“There were people for whom we could not move fast enough, and [others] who could have taken a six-month sabbatical to go and learn what they needed to learn in order to feel caught up to speed on the stuff we were talking about.”

—Anne Eidelman

Staff was in agreement that Blue Engine struggled with how to deeply understand their values and translate them into practice.

“We did a lot of work to define DEI — I felt like just defining those things didn’t make it more authentic or organic, and the actions just became a little more robotic...there ended up being holds on calendars for DEI, and then we would try to figure out what content went in there. It would be more valuable to understand what having these conversations would mean to the staff, and what outcomes would come from having these conversations.”

—Anonymous Staff Member

Recognizing the need to invest in additional capacity to propel DEI work forward, Blue Engine established a new Director of DEI role. However, without clarity on the specific priorities they needed to advance around DEI, this hire wasn’t set up to lead effectively.

“We had been getting a lot of external support, but the leadership team wanted to do more on this, so they transitioned someone internally into that role full time. I don’t think we were far enough along in our own journey to understand what the work should be or look like, and that did not set her up for success. She had a ton of knowledge, skills, and experience with [professional development], but I don’t think she was set up to understand what our organizational goals were, and the leadership team didn’t know, either. It was a very messy year.”

—Jessi Brunken

“We had created a DEI position, filled it internally, and I don’t think we as a leadership team were clear [on] what we were trying to do. The role wasn’t scoped and it wasn’t embedded in the umbrella of organizational strategy and goals. We set up the person for failure.”

—Anne Eidelman

In the midst of these challenges with translating values to practice — right before Anne took over for Nick as CEO — leadership had to make some very tough decisions around cutting positions due to budgetary constraints. In Spring 2017, layoffs happened on the heels of other leadership-level transitions earlier that year. This left staff with the impression that the process had been opaque and top-down, and trust among staff suffered.

“We were very destabilized — I think the culture had really eroded that year. The layoffs blew everything up. There was really a lack of trust, and [everyone was] feeling a lack of transparency. [Anne] stepped into a really hard moment.”

—Jessi Brunken

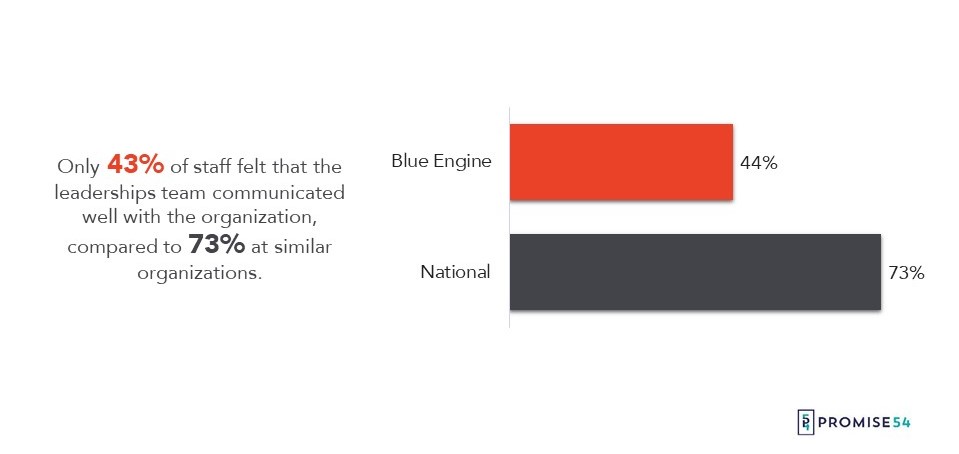

In 2018, following a difficult year of staff transitions and lagging trust that impacted staff culture, Blue Engine paused to thoughtfully determine their highest leverage next steps. Specifically, Blue Engine decided to participate in Promise54’s DEI Accelerator program, and the team took the Promise54 DEI Staff Experience Survey to get clear on where and how to focus their efforts.

While overall, Blue Engine fell within the “Advanced” organizational profile, they saw lower staff perception of inclusion than equity and diversity.

As Blue Engine looked deeper into their January 2018 Promise54 DEI Staff Experience Survey results, they saw the biggest gaps around communication and transparency. Only 44% of staff said, “Our leadership team communicates well with the organization.” Further, feedback from staff indicated mistrust and desire for greater transparency around how decisions were being made.

Blue Engine leadership now knew: they needed to hone in on engagement and transparency in relation to communications and decision-making to rebuild the trust that they knew to be foundational to staff experiences of inclusion and equity.

In response to their survey findings, the leadership team formalized a specific goal in 2018: “[Blue Engine] will improve communication and transparency with a goal of creating a more inclusive staff culture, as evidenced by staff experience survey data.”

To accomplish this goal, the leadership team aligned on their upcoming priorities; explicitly delineated the process by which leadership would seek and incorporate staff feedback; and identified when and how leadership would communicate processes and decisions to staff along the way. Anne shared leadership’s commitment and plan with staff at the beginning of the year.

Leadership had some real opportunities to enact this commitment, as Blue Engine had complex programmatic decisions to make for the following year. Leadership gathered critical staff input from a cross-functional working group. Blue Engine staff heard monthly updates from leadership on the decision-making process and the factors they were weighing. They were clear and transparent about what they knew, when they knew it, and any pending information or decisions. Leaders iterated on this process throughout — gathering information, incorporating staff perspectives, and consistently sharing information and updates.

In 2018-19 — unlike two years prior, when staff felt that decisions had been made “behind closed doors” — staff shared formal and informal feedback that they felt both informed and included along the way, and that they understood how decisions were being made. Staff now perceived decisions as transparently and fairly made, and Blue Engine’s Net Promoter Score was the highest it had been in years.

“I also felt that there was a lot of transparency and the leadership team brought the organization along on that journey as much as possible, which was greatly appreciated. The emphasis on rationale and how we got here helped my own clarity and increased the connection I feel to [Blue Engine] even more.”

—Anonymous Staff Member

“I deeply appreciate the transparency of the leadership team as well as being invited to share thoughts, ideas, questions, and feedback. Understanding the path of the organization helps me ground my work in a larger vision, which is deeply motivating and interesting.”

—Anonymous Staff Member

During a 2018 quarterly pulse check survey, staff raised questions around attrition rates over the last couple of years (in general and by demographic). In response, the leadership team analyzed three years’ worth of staff data. This included retention rates and demographic data, which leadership shared out at the next staff meeting, and facilitated an honest conversation with current staff about historical staff culture and turnover challenges. Staff shared that it was a hard conversation to have but appreciated the immediate response and opportunity to engage.

“Leadership provided a space for transparent communication, processing, and discussion around staff retention, [staff survey data], and org health.”

—Anonymous Staff Member

“[I appreciated] the super transparency around turnover and where the challenges the organization faced over the years [came from]. I got to learn about the organization’s past and while I’m not sure I personally put down comments on turnover, I was also curious — and to see the leadership team respond so readily to those questions/concerns always makes me happy to be working here.”

—Anonymous Staff Member

“At every moment, our [leadership team] has worked to build structure and intentionality around communicating and incorporating feedback; we consistently ask ourselves, ‘What should we be sharing with staff right now? Who do we need to get input from?’ We now err on the side of telling staff as much as possible as early as possible; we have rebuilt trust all around — it has been mutually reinforcing, as both the culture and the work itself have gotten stronger.”

—Anne Eidelman

To further enhance the alignment of work and transparency in communications, Blue Engine also established definitions for diversity, inclusion, and equity during DEI Accelerator work with Promise54 in 2018:

Graphics Provided by Blue Engine

All these changes around implementing their bedrock DEI values have implications not only for internal staff but also for external stakeholders including BETAs, partner schools, administrators, and funders. How has Blue Engine navigated this added layer of complexity?

Shifting metrics toward student growth — while better aligned with Blue Engine’s bedrock DEI values — has continued to pose significant challenges for the organization’s interaction with funders, partner schools, administrators, and others who may define student success by more traditional measures. Even though staff were on board with the shift ideologically, they’ve experienced tension around implementation.

“We made this internal shift to a north star around gains for all students, and yet two years later, I’m still struggling and don’t think even all of our funders really understand our choice, rationale, or evaluation methodology...I think we’re still figuring out what it means on the ground. How are we trying to shift and influence mindsets of teachers and principals in schools, and what role do we play? I think that is still stirring for us and something we need to continue to grapple with.”

—Anne Eidelman

Blue Engine has faced another challenge in living out their values — this time, in supporting BETAs to navigate the interruption of inequities in the classroom. During four weeks of summer onboarding, BETAs start to reflect on the “individual and collective why” that brings them to the work. BETAs participate in DEI-specific training anchored in Blue Engine’s core values — especially their bedrock DEI value — to build and reinforce mindsets that reject the status quo of the current education system. Since each BETA enters with varying experiences, exposure, and understandings of systemic oppression, Blue Engine spends time in facilitated conversations unpacking race, racism, and biases, and how they show up in classrooms. The training both supports BETAs and sets a higher bar for how they’re expected to respond to inequity. This can put BETAs in a tough position, given their limited positional power and need for additional support in identifying opportunities for structural change.

“It was really powerful to do work with folks in our org, but some of the challenges we ran into were what did that mean for our [lead] teachers who didn’t necessarily go through the same training? What did it mean for BETAs to ‘interrupt?’...It’s a hard skill, and I don’t think we’re totally equipped to instruct others how to do it yet because we’re still working on it ourselves, but that became part of the nomenclature of our bedrock DEI value, which I think is important and impactful.”

—Anne Eidelman

“When BETAs would encounter teachers or principals who were saying damaging things about children, they started to feel that tension and they would report that back to us and ask us, ‘What should I do?’ And we train them to have those conversations, but then there’s a tension with positional power — we lost a lot of [BETAs] from that tension — as much as we wanted to do the work, we didn’t have that power over our partners. Partner teachers weren’t a part of that diversity training.”

—Erick Roa

“A lack of skill is in part a barrier, but it’s not the biggest. It’s not quite knowing or identifying what’s at risk. Is this worth it? It’s one thing to know the skills or when an interruption needs to happen; it’s another to navigate when it’s worth it.”

—Emily Walsh

Many open questions remain for Blue Engine, as the team works to figure out:

These are just some of the tensions that have surfaced as Blue Engine reimagines their role in a system historically characterized by exclusion and inequity. Staff like Renise Williams acknowledge this: “There’s a natural tension when trying to create a world where there is actual inclusion and equity, and what it looks like to navigate existing systems.” And Blue Engine remains committed to working through that tension.

Given these lessons and the progress Blue Engine has made over the past few years in their DEI journey, what is the organization focused on next?

Blue Engine has continued to work on culture-building and has focused on incorporating DEI explicitly into their strategic plan. This summer, the team retook the Promise54 DEI Staff Experience Survey to see whether there were any changes resulting from their recent work. The results? The organization is moving in a positive direction:

Several of Blue Engine’s measures, including their Net Promoter Score, increased considerably since their last survey administration:

At the same time, the survey highlighted challenges in sustaining the amount of reflective training and dialogues staff once engaged in:

The survey results are informing Blue Engine’s people approach moving forward:

“We are wholly committed to creating an equitable and inclusive environment that attracts and retains a diverse team that thrives and maximizes Blue Engine’s impact for students across the country. We will invest in our people, culture, and systems to create an environment where people want to stay and grow.”

And in 2019-20, Blue Engine will develop their first-ever multi-year DEI plan, including goals, strategies, and concrete actions they’ll take to advance their overall mission.

As the team sees a positive trend in staff experience, Blue Engine is still grappling with a number of questions, including:

All in all, Anne acknowledges the nonlinear route Blue Engine has taken:

“It’s not a smooth thread. When I look back four and a half years ago, the staff has changed, the spaces we create have changed...There’s more to do, but [we’ve made] more space to practice radical empathy and show up for kids and [for our]selves in a different way.”

—Anne Eidelman